August 1843 - Ada’s Translation & Notes

Ada’s Notes “cover algebra, mathematics, logic, and even philosophy; a presentation of the unchanging principles of the general-purpose computer; a comprehensive and detailed account of the so-called ‘first computer program’; and an overview of the practical engineering of data, cards, memory, and programming” (Hollings et al.).

WHAT ARE ADA’S NOTES?

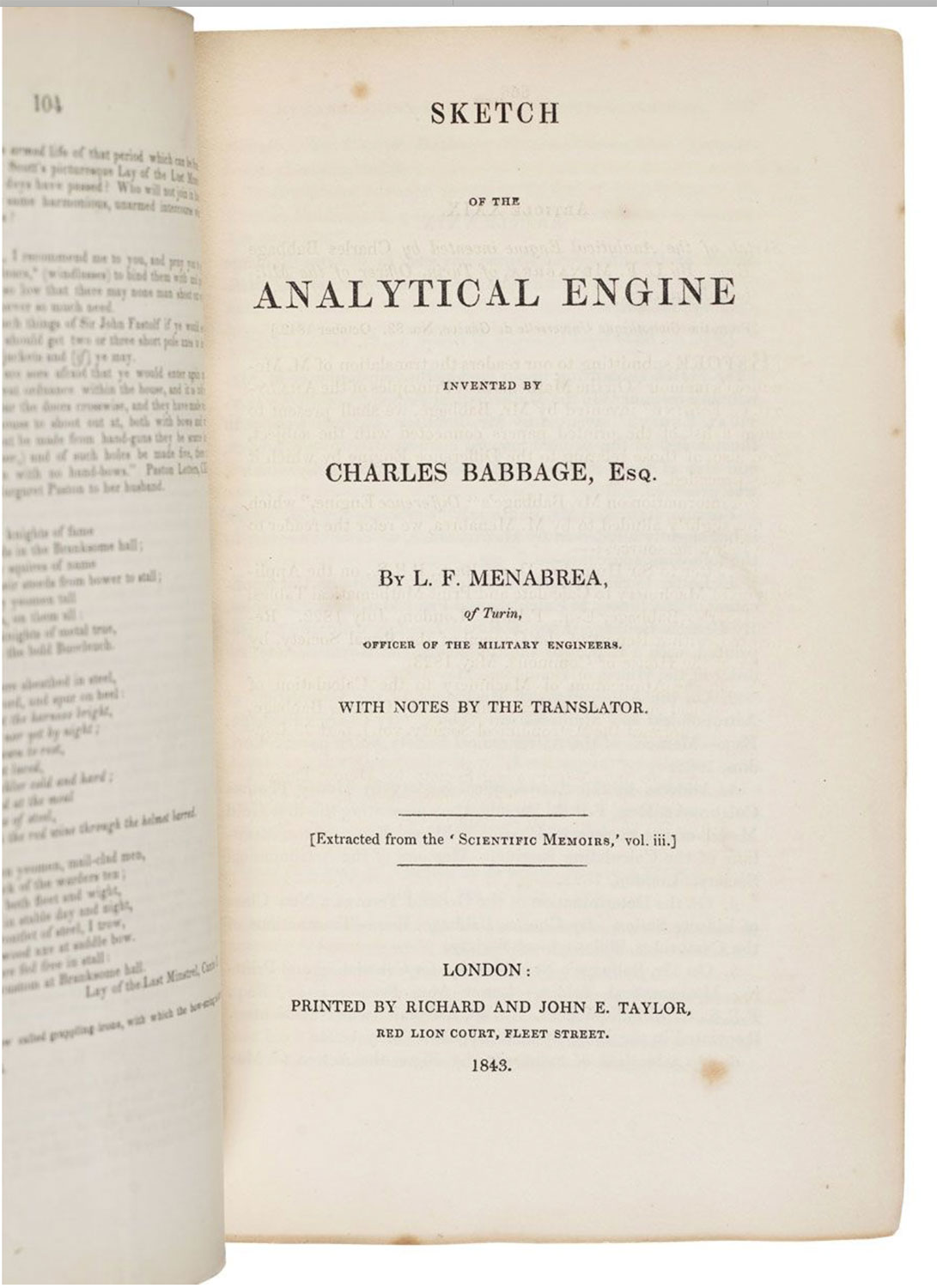

In October 1842, Luigi Menabrea, an Italian military engineer and future prime minister of Italy, wrote an article Babbage’s Engine. Charles Wheatstone, a friend of Ada’s thought it would be a good idea for Ada to translate this article, from French into English. According to the book Ada Lovelace: The Making of a Computer Scientist, Babbage suggested she also expand on her translation with appendices, known as Ada’s “Notes.”

In August 1843, after corresponding regularly with Babbage, and after months “of furious effort by them both, Ada’s resulting paper was published in Taylor’s Scientific Memoirs. It was signed only with her initials, A.A.L.” (Hollings et al.).

Ada’s paper comprised her translation (25 pages) along with forty-one pages of detailed notes. Babbage never finished the Engine, but it is Ada’s Notes on this Engine that is her greatest achievement and contribution to mathematics and computer science.

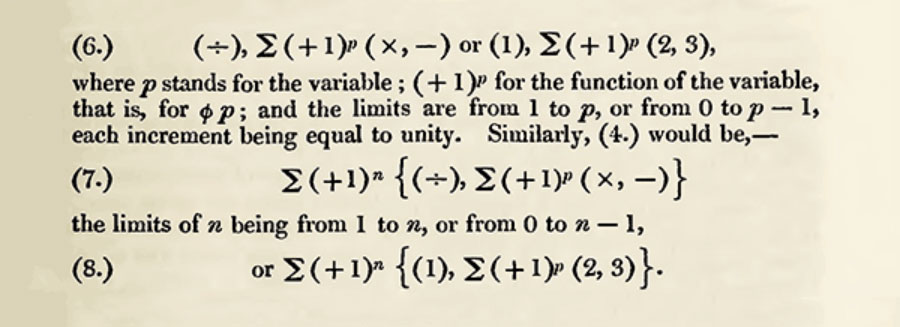

Ada goes through how a sequence of specific kinds of computations would work on the Analytical Engine, with ‘Operation Cards’ defining the operations to be done, and ‘Variable Cards’ defining the locations of values. Ada talks about ‘cycles’ and ‘cycles of cycles, etc’, now known as loops and nested loops, giving a mathematical notation for them” (Wolfram).

QUOTES ON WHY ADA’S ‘NOTES’ ARE SO IMPORTANT TO MATH AND SCIENCE EVEN TODAY

“Lovelace’s paper is an extraordinary accomplishment, probably understood and recognised by very few in its time, yet still perfectly understandable nearly two centuries later” (Hollings et al from Science Focus).

“she went beyond the “thinking” machine into biophysics and mathematical modeling of biological processes” (Taranovich)

“… her notes ‘are mind-blowing with regard to the [mathematical] concepts they contain'” (Simon and Maxfield).

“… when the English version of the piece was published in 1843, much of it was Lovelace’s own work. She added workings to show how Babbage’s machine could perform calculations on its own, and suggested that it had the potential to convert music, pictures and text into digital form” (Crockett).

“In Note G of her elaborate paper, Lovelace wrote of how the machine could be programmed with a code to calculate Bernoulli numbers, which some consider to be the first algorithm to be carried out by a machine and thus the first computer program. (Klein)

“Her Notes anticipate future developments, including computer-generated music” (San Diego Supercomputer Center).

“… the article contained statements by Ada that from a modern perspective are visionary. She speculated that the Engine ‘might act upon other things besides number… the Engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent’. The idea of a machine that could manipulate symbols in accordance with rules and that number could represent entities other than quantity mark the fundamental transition from calculation to computation. Ada was the first to explicitly articulate this notion and in this she appears to have seen further than Babbage. She has been referred to as ‘prophet of the computer age’. Certainly she was the first to express the potential for computers outside mathematics.

“ADA LOVELACE” AT COMPUTER HISTORY MUSEUM

EVEN BABBAGE WAS AMAZED AT HER NOTES OF HIS OWN MACHINE

Babbage wrote the following about Ada to Michael Faraday “that Enchantress who has thrown her magical spell around the most abstract of Sciences and has grasped it with a force which few masculine intellects (in our own country at least) could have exerted over it.” (Hollings et al from Science Focus)

“All this was impossible for you to know by intuition and the more I read your notes the more surprised I am at them and regret not having earlier explored so rich a vein of the noblest metal.” — Charles Babbage

Excerpt from Note A – the Note that Babbage asked her not to change.

EXCERPTS FROM ADA’S NOTES IN 1843

“Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent.”

“It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis; but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths. Its province is to assist us to making available what we are already acquainted with.” Over 100 years later, in 1950, Alan Turing challenged this and even called it “Lady Lovelace’s Objection.”

Ada stated Babbage’s Analytical Engine “… was suited for ‘developping [sic] and tabulating any function whatever. . . the engine [is] the material expression of any indefinite function of any degree of generality and complexity.’

“We may consider the engine as the material and mechanical representative of analysis, and that our actual working powers in this department of human study will be enabled more effectually than heretofore to keep pace with our theoretical knowledge of its principles and laws, through the complete control which the engine gives us over the executive manipulation of algebraical and numerical symbols.”