June 5, 1833 - Ada Meets Charles Babbage

The first party Ada attended was at the house of mathematician Charles Babbage. Babbage’s “upscale parties at his large … house in London attracted such luminaries as Charles Dickens, Charles Darwin, Florence Nightingale, Michael Faraday and the Duke of Wellington” (Wolfram). Babbage, who was forty-one-years-old, must have been impressed enough with Ada at that party because he invited both Ada and her mother back to his house to view a demonstration of his Difference Engine.

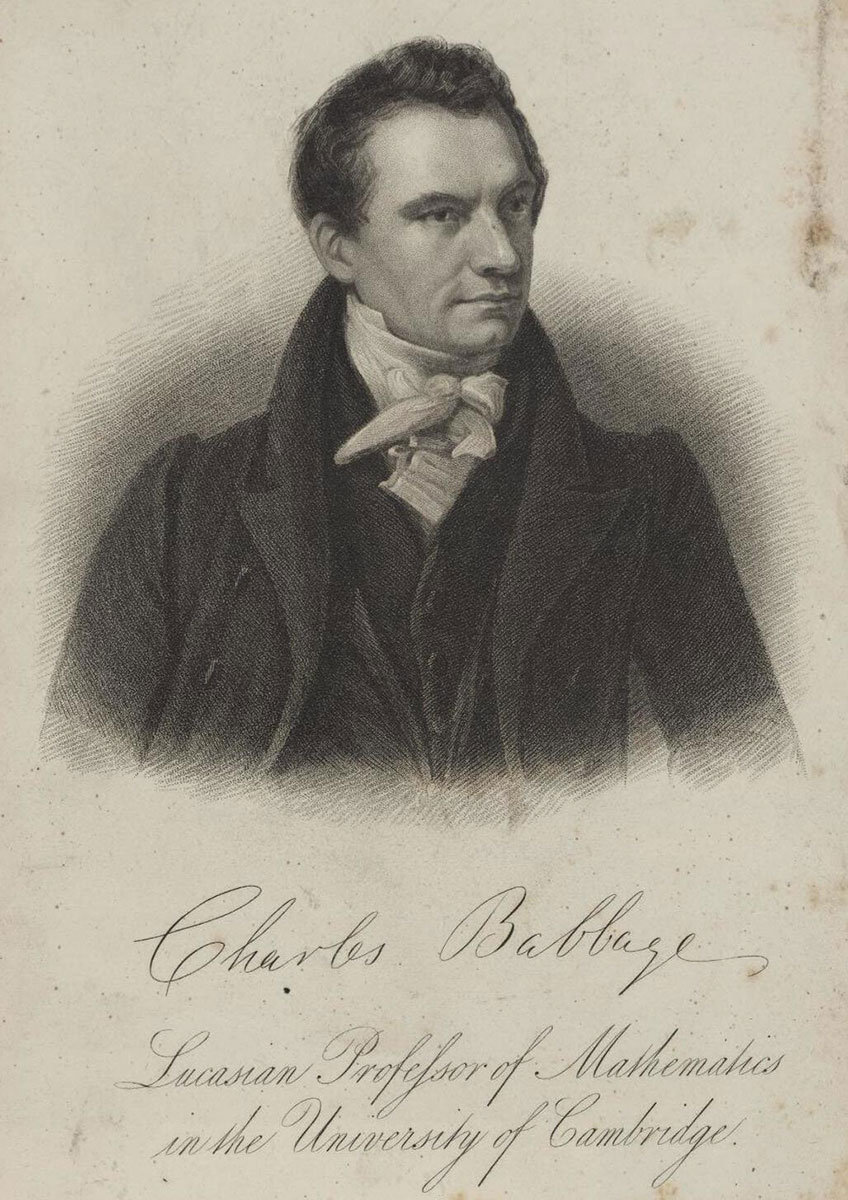

Charles Babbage by Antoine Claudet c 1847-51

The Difference Engine was “… the first device we might consider to be a computer in the modern sense of the word …” (Simon and Maxfield). It was Ada’s encounter with this device, “… the Difference Engine [that] seems to be what ignited her interest in mathematics” (Wolfram).

Babbage, who had previously studied mathematics at Cambridge, and also founded the Analytical Society (Cambridge Philosophical Society) with his friends John Herschel and George Peacock, “a pioneer in abstract algebra,” sought to make a machine that could “compute any polynomial up to a certain degree using the method of differences, and then automatically step through values and print the results, taking humans and their propensity for errors entirely out of the loop” (Wolfram).

At the time, “tables were made by human computers, with the work divided across a team, and the lowest-level computations being based on evaluating polynomials (say from series expansions) using the method of differences” (Wolfram).

After Ada’s meeting with Charles Babbage, she remained lifelong friends with him, and Ada’s “letters to Babbage are full of details of the mathematics books she was reading, the progress of her children, and the antics of her dogs, chickens, and starlings” (Hollings et al from Science Focus) in addition to their collaboration during her translation of Menabrea’s article on the Analytical Engine.